Written by Frew Tibebu

In March of 1980, Frew Tibebu, a refugee in the Republic of Djibouti, walked into the U.S. Consulate office seeking a student visa to study in Washington, D.C. In his possession was the blue United Nations passport, a one-way ticket to Washington, D.C., and a completed official Form I-20 from Sanz College in Washington, D.C. He felt confident about his chances of receiving a visa and even discussed throwing a going away party, as was the fad of the times, with couple of his friends who worked at the consulate office.

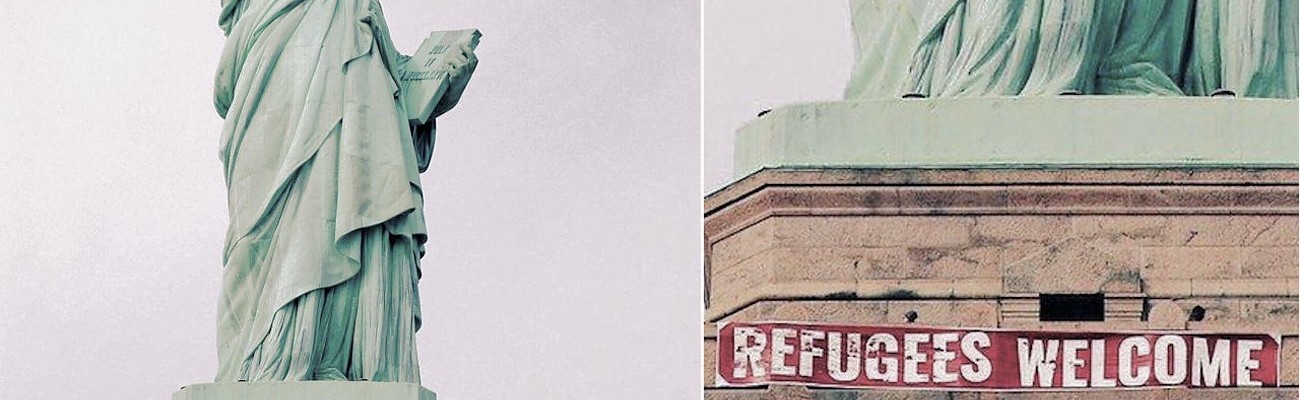

Image credit: Doodlebug

He was told to leave all his documents at the office and return the following Monday. Then he received the grim news that no student or tourist visas would be issued to any migrants leaving Djibouti and the rest of East Africa going forward. Instead, all potential migrants would be processed by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in coordination with the U.S Consulate within the following six months in order to travel as permanent immigrants. He felt as if he had been stabbed with a knife. “Why now?” he sighed, “Why me?”

Unbeknownst to him, in the United States, the people and their government had passed a law: The United States Refugee Act of 1980 (Public Law 96-212). The act amended earlier immigration acts and addressed the need for comprehensive and uniform provisions for effective resettlement and absorption of refugees in crisis. It raised the number of refugees admitted to the United States each fiscal year. The act received bipartisan support in the U.S. Congress and was signed into law by President Jimmy Carter on March 17, 1980. To this day it remains the “gold standard” for people and countries to act morally, responsibly, and with compassion when confronted with people who are violently forced to flee their homes to save their lives and the lives of their families in alignment with the U.N. treaty standards. In 1980, the year the act took effect, there were a total of 207,116 refugee admissions, most of them from Vietnam (Source: Table 13, 2018 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics). Today, in 2020, the world faces the highest number of displaced people on record at 70.8 million according to the U.N. Refugee Agency. The U.S. lags behind its humanitarian commitment, having brought down the ceiling in 2020 to 18,000 refugees, close to the statutory ceiling of 17,400 that Congress repealed in 1980, rather than adjusting to a scale more suitable for today’s global refugee crisis. In a further development, the current administration indicated that it will further cut the number of refugee admissions to 15,000 for the fiscal year that beginning October 1, 2020 in a letter sent to Congress just before the expiration of the statutory deadline. While the 1980 Refugee Act allows the president to set the maximum number of refugees allowed entry at the beginning of each fiscal year, this action further undermines the United States image as a beacon of hope for oppressed people around the world.

By the time Frew received what he thought was bad news from the U.S. Consulate, he had been living in Djibouti for about a year and was exhausted from the unrelenting heat and lack of prospects for his future. For the next couple of weeks, he was in a state of despair and depression. To take their minds off things, he and a few of his fellow refugees were hanging out at the beach by the coast of the Gulf of Aden. Their presence on the beach drew the attention of the local police. Without any explanation and forewarning, the police approached, loaded them up into their vehicles, and transported them to the local prison, despite the fact that most of them had the blue United Nations passports and temporary passes called laissez-passer from the authorities in Djibouti. Their crime was idling at the beach while refugees, or just simply animosity towards refugees. Rumors had been circulating that refugees would be sent back to the Ethiopian border, and their arrest made Frew and his friends fear that the rumors might be true. However, while some of the refugees were locked up to three or four days, Frew was lucky to be released the same day when his host family showed up at the prison demanding his release.

Image credit: Frew Tibebu

For the next few months, things remained quiet. No one was leaving Djibouti, but sometime in July the UNHCR office started bustling with activity. The word on the streets in Djibouti was that soon the office would start interviewing Ethiopian refugees. Before long, the process started and translators were deployed to help those with language barriers. Almost everyone who was of Ethiopian descent and who wanted to leave Djibouti was interviewed. The consensus among the international community was that Ethiopia was facing a refugee crisis unlike anything seen in the recent past. Large-scale international migration among Ethiopians was a relatively new phenomenon that needed a different solution than what was required to address inter-border displacement fueled by drought and ethnic conflict. Debates ensued as to who was entitled to emigrate, and the line was blurred between those who left because of political factors and those who left for economic reasons. It was becoming evident to the refugee community that potential asylum seekers had to show a well-founded fear of persecution based on race, religion, politics, or belief system if they were to return to their home countries. The translators filled in the gaps as they saw fit to align with the interest of the interviewees.

While hundreds of Ethiopians had come to Djibouti as diplomats and business people, and some owned bars and restaurants, there were also those who came hoping to escape economic hardship and those who sought their fortunes in the world’s oldest profession. However, the recent influx was fueled mostly by the draconian measures taken by Mengistu Hailemariam’s administration to wipe out opposition to the military junta (known as the Derg) that had deposed the Emperor and begun a violent campaign to consolidate its power. In short, the recent migration was mainly fueled by political instability and by fallout from the Derg’s vicious 1976-1977 political repression campaign against the opposition, called the Red Terror. Frew’s case fell in this category. As a high school student recently returned from national service (Zemecha), he had joined a youth resistance movement against military rule that eventually led to his arrest. He remembers the words of the prison administrator, Hamsa Aleka Teshome, at the time of his final release from prison: “If you ever get caught again, it does not even have to be associated with politics, you will be executed.” He felt this was a death sentence while still breathing, and it made the decision to flee to Djibouti much simpler. It was a decision made in order to escape further persecution from the Derg. It was a gamble on his life.

The UNHCR’s interview process neared its’ completion in the month of September, coinciding with the Ethiopian New Year celebration in the month of Meskerem (Enkutatash). At this time, the rainy season ends and is followed by spring, and the Adey Abeba (yellow daisy flowers) shoot up from the ground in their brilliant yellow, bringing with them hope for a better future ahead and ushering in the new year.

Most Ethiopian immigrants have taken an indirect path to pursue emigration to the West, first fleeing Ethiopia to a neighboring country as a transitional first step. It is difficult to account for those that perished along the way. In one survey of Ethiopian immigrants in the United States and France, Tasse’ Abye found that the majority spent between one and three years in countries on Ethiopia’s periphery, mainly Djibouti, Sudan, Kenya, and Somalia. Once travelers had survived the journey to the refugee camps in these countries, they had a chance to resettle in the U.S., Canada, Australia, The Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Sweden, and the Federal Republic of Germany.

In mid-September the names of refugees were posted in the office windows of the UNHCR. Six months after he entered the U.S. Consulate office, and a year and a half since he walked to a refugee camp in the border town of Dikhil, Djibouti, Frew was welcomed to the United States on September 26, 1980, alongside hundreds of Ethiopian migrants, as lawful permanent residents (LPRs). Concurrently, similar programs airlifted Ethiopian refugees from other bordering countries like Sudan, Kenya, and Somalia.

According to the 2018 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, 12,927 Ethiopians obtained lawful permanent resident status between 1980-1989. In the following decade that number swelled to 40,097. To put it in perspective, only 3,732 persons of Ethiopian origin entered the U.S. and obtained a lawful permanent residence in the 70 years prior to 1980. In the majority of the cases, political factors or events were given as the reason for emigrating. This wave of mass migrants to the U.S. and other Western countries marks the beginning of a more permanent Ethiopian diaspora, thereby changing the nature of and relationship to the homeland.

A day after he arrived in New York, Frew joined his relatives in the Washington, D.C. suburb of Silver Spring, and a close-knit group of Ethiopians numbering in the thousands who lived mostly in the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area. Night life revolved around visiting the only two Ethiopian restaurants that had sprung up in 1978: the Blue Nile Ethiopian restaurant off 16th Street, and Mamma Desta’s on Georgia Avenue about a mile from Howard University. Between the two, Mamma Desta’s was credited with starting America’s love affair with Ethiopian food. In the meantime, Washington, D.C. was emerging as a global food mecca, and Mamma Desta’s was receiving rave reviews despite the establishment’s sub-par décor. In April 1978, Baltimore Sun writers Tom Horton and Helen Winternitz (who had spent five years in Ethiopia) declared that Mamma Desta’s offered “the best Ethiopian meal this side of Addis Ababa,” according to Mayukh Sen, whose upcoming book about the immigrant women who have shaped food in America is set to be published in Fall 2021. Today, Ethiopian food has gone mainstream: it is widely available in major cities across America and is hugely popular among health conscious Americans as an alternative vegetarian offering.

Over the intervening years, the Ethiopian diaspora population has ballooned to hundreds of thousands according to statistics from the Office of Immigration and Homeland Security. As their number grows, its impact is felt in both their second homes and in their country of origin. The diaspora community is strategically positioned and engaged in nation building through the sharing of resources, knowledge, and ideas. It would not be a stretch to say the diaspora is a modern day caterpillar. Through hard work and resiliency, the diaspora community has succeeded in playing a key role in global growth while maintaining emotional, cultural, and spiritual attachments to the homeland.

Image credit: Frew Tibebu

Immediately after his arrival in the U.S., Frew started working and going to school. In August 1986 he graduated from the University of District of Columbia in Business Administration. Just months prior, on July 4, 1986, he became a naturalized United States citizen. In September 1989, he left the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area and moved to northern California. On April 10, 1998, he married his wife Debbie in a Tracy, California courthouse. Today, Frew works as a real estate professional in Tracy and the California Central Valley. His family consists of three children: two sons and one daughter, as well as five grandchildren. He considers raising a family one of his top achievements alongside his philanthropic work promoting literacy in his birth country through the nonprofit Ethiopia Reads, and co-founding the Ethiopian Diaspora Stories Project.

On this 40-year anniversary, Frew would like to acknowledge the following people and organizations for his successful transition to his second home, America:

- First and foremost, I praise God for sparing me from the mass killings that took place in Ethiopia prior to my departure, and for my safe passage to Djibouti and later to the United States of America. His faithfulness has not left me. I would like this anniversary to be a time to reflect and remember all those whose lives were unjustly cut short and to honor their families for the anguish and pain they endure to this day.

- My direct family: my mother, my sisters, and my second mother, Etagegne. My neighbors, Seble, Atnaf, Woinshet, and Dehab. My relatives Atatu Daba, Gash Negatu, Tsige Lakew, and the entire family. These are some of the people who helped me survive the prison experience, but I am sure there may be more.

- Amune (Uma) for arranging an escape route to Djibouti. Lula Gonji and Nejib for hosting me in Djibouti.

- Countries that have generously hosted me and other refugees, starting with those on the periphery of Ethiopia: Sudan, Kenya, Somalia, Djibouti, the U.S., Canada, Australia, Israel, Sweden, Germany, France, Greece, Belgium, Switzerland, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, the Netherlands, Norway, Italy, the United Arab Emirates, etc.

- The United States Consulate in Djibouti and neighboring countries for coordinating with UNHCR toward a successful transition.

- The United Nations High Commissioner For Refugees for being a staunch ally and advocate in this difficult journey and facilitating this large-scale human migration.

- International Catholic Relief Services for covering the cost of plane tickets for thousands of refugees and later disbursing weekly allowances to them in the U.S.

- The government and people of the United States of America for passing legislation that was favorable toward refugees, thereby extending their generosity and compassion toward the most vulnerable people around the globe. The Refugee Act of 1980 received bipartisan support in the U.S. Congress and was signed into law by President Jimmy Carter on March 17, 1980, 40 years ago.

- My relatives in the U.S.: my step mother Aster, my aunties Roman and Menna, and many close friends–Seyoum, Liz, Moges–who received me with open arms.

The cause of freedom is not the cause of a race or a sect, a party, or a class–it is the cause of humankind.

anna julia cooper

As I know firsthand, you have given so much to your fellow Americans and also to the country you left behind. Reading this story of those low moments of despair makes me teary eyed. What a treasure that law has been to me!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks jane! The feeling is mutual. God works in mysterious ways, we had no clue what plans he had for us as we were shut off from the rest of the world. We knew about the Iranian Hostage Crisis that started in November 1979 that was still ongoing at the time, and the Vietnamese humanitarian and migration was also at its peak. It didn’t cross our mind that anyone will be looking to take care of us.

LikeLike

Thank you for sharing your story. It is amazing how a turn of events can change lives way into the future. I feel blessed that our paths have crossed. This is a story of courage and the willingness to create good out of every circumstance you are given.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What an inspiration. Thank you for sharing your story countless times. Your resilience throughout all of your life’s obstacles is part of what makes me who I am today. Your strong faith in God is what has brought you this far and He knows your work here on Earth is not done yet! Love you, Dad!

LikeLike

Carrera-You know me well to know that I was a reluctant Dad, because I was afraid that I would mess up and disappoint the people that God placed in my life, but for you to call me Dad fills me with pride. If I were asked what was my proudest accomplishment, it would be playing Dad for you and Henre’ and a husband to your mom. God thought me to be patient, and to wait on him to guide my everyday interactions, and always to try to do good.

LikeLike